Home / Continuing Studies News / Reconstructing Holocaust histories through visual narratives

Reconstructing Holocaust histories through visual narratives

with UVic Professor Charlotte Schallié

By Therese Eley, Marketing Services

"Imagine saying to a Holocaust survivor, 'We'd like to do a comic about your life,'" chuckles Charlotte Schallié, professor of Germanic Studies and chair of UVic's Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies.

It seems, at the surface, like an absurd request: to take survivors' trauma and marry it to an art form that is generally associated with light-hearted comedy and even triviality. But, in truth, that is an over-simplification, and indeed a misrepresentation, of the series of graphic novels that Charlotte and her team created.

Charlotte first became interested in the graphic novel genre through her teenaged son, a reluctant reader who was really interested in graphic novels. "So, I just kept buying them for him. Then I got very interested in them and found that there is a whole host of graphic novels that deal with socially relevant issues, social justice issues," she reflects.

Eventually she came across Maus by American cartoonist Art Spiegelman, which depicts a son interviewing his father about his experiences as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor. She incorporated it into the curriculum of a Holocaust Studies course that she was teaching, and found that the students were really engaged and excited about exploring serious subject matter through this artistic form.

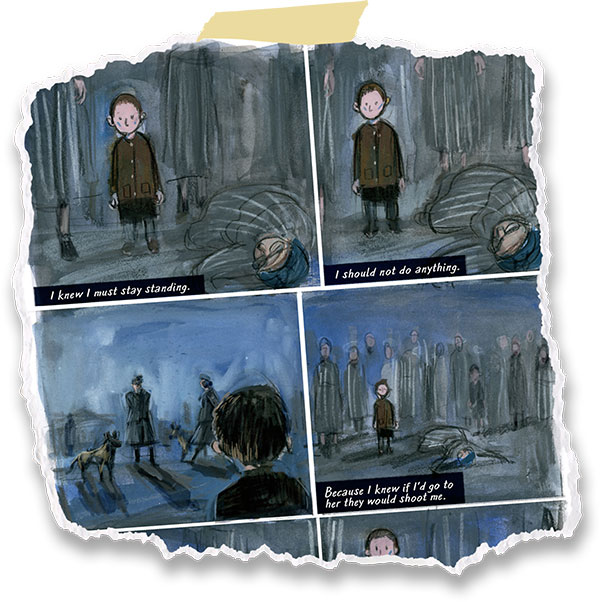

Artwork: Barbara Yelin

Artwork: Barbara YelinThis got her thinking about creating a project that pairs artists with child survivors to co-create three graphic narratives together. "It is such a fascinating art form because it allows a multilayeredness of the story. It really allows us to show non-verbal elements, such as emptiness or trauma or just nothing because the survivor cannot remember, or the artist simply cannot draw such a horrific scene. As in films, sometimes what they [the survivors] don't say is as powerful as what they do say. And the reader or the viewer complements it, so they become part of the meaning-making process as well," she says.

Like many historians, Charlotte has often used more traditional methods to interview survivors. In these projects, she realized that asking people a series of scripted questions just extracted a narrative that she was already expecting or looking for. Engaging artists in the process changed the research by actually gathering the story the survivor needed or wanted to tell.

As Charlotte describes it, "We can do a lot of harm with these interviews. With these Holocaust survivors, it is extremely difficult for them to give their testimony, even when they are experienced testimony givers, because it is so intimate and personal. But one important thing we found was artists ask very different questions than what a more traditional interviewer would ask, because if you have to draw a scene you need to ask questions like 'What was your hairstyle at the time? What was the colour of your coat?' etc. So, the survivor has to get into different recesses of their brain and that, we saw, could bring up very difficult material that they may have repressed.”

Although the project brought about three graphic novels, it is clear that, for Charlotte, a key take-away of the project is what was learned through the process of collecting these stories in a trauma-informed and ethical way.

"We cannot just say, 'Here is the finished project! Look at these beautiful graphic novels; stories of heroism, amazing work!' No. They are beautiful work, but we need to talk about the process, the costs involved in remembering stories like this. I think with this project, one important aspect is we want to share our methodological process so others can benefit from it and perhaps draw on it in their own work with trauma survivors."

This was not an easy project to complete. It required a lot of courage and trust on behalf of both the survivors and the artists. It required really understanding the impact of trauma, and a commitment to an ethics of care and compassion. There were difficult obstacles that threatened to side-track everything. So why do it?

"With mass atrocity, the more I know, the less I understand," Charlotte reflects. "Each testimony is of critical relevance, but it doesn't necessarily facilitate engagement. How do we really bring about change? How do we get a person who reads this to say, 'Oh my god, I need to be more attuned and more mindful to what is going on in my world! I need to do something. I cannot pretend it isn't happening.' It’s so awful, so unimaginable, that it makes us shut down. It creates apathy because it is so difficult. I think art is an incredible way to humanize these testimonies and engage people because it triggers emotions in people and has them experience the testimony in a different way."

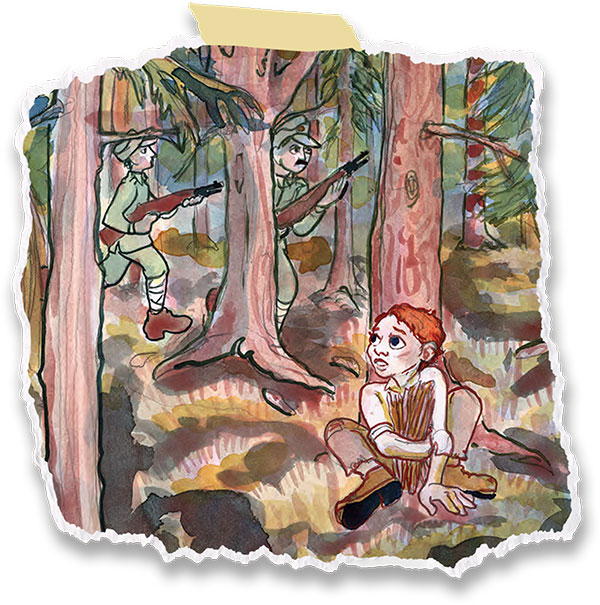

Artwork: Miriam Libicki

Artwork: Miriam Libicki"You know how we say 'never again?' Well that's not going well, this happens all the time. So, to not tell it…I cannot not tell it! I guess because to some extent I have a personal obligation but also as a human being and as a scholar, I think we cannot let ourselves ever forget. The Holocaust didn't happen overnight, there were early warning signs. There was a slow process that started from targeting human beings, to segregating them, to dehumanizing them, and this can happen any time and it will happen again. We cannot afford to ever forget."

Watch video lecture

Dr. Charlotte Schallié recently participated in the Deans' Lecture Series and presented on this research project. Watch her lecture, titled "But I Live – Three Child Survivor Stories of the Holocaust".

- Posted November 30, 2021

Visit Registration

2nd Floor | Continuing Studies Building University of Victoria Campus 3800 Finnerty Road | Victoria BC | CanadaTel 250-472-4747 | Email uvcsreg@uvic.ca

2024 © Continuing Studies at UVic

Legal Notices |

Sitemap